The Republic was sick. Its once-innovative machine of government, built for a provincial yesteryear, was ill-equipped for the reality of international empire. In an increasingly multi-polar world, the functions of state remained the exclusive province of an ancient and conservative aristocracy. Money bought election to high office; high office led to military command; military command led to plunder, wealth, and glory. Officials served one-year terms, hardly sufficient to accomplish any agenda, and were open to prosecution by rivals after leaving office. A constitution rife with loopholes allowed the system to be compromised, again and again, by unscrupulous and corrupt politicians.

Rome may have been a republic, but it was hardly a democracy. Disenfranchisement was the rule for its vast population of women, non-citizens, and slaves. Slave revolts and the Social War for Italian enfranchisement shook the Italian Peninsula of the First Century B.C. At the same time, threats loomed at the margins of the growing empire. The King of Pontus menaced Rome in the East, engineering the simultaneous massacre of at least 80,000 Romans and Italians living and working in Greece and Asia Minor around 88 B.C.

And so the Republic trembled when an army appeared at the gates of Rome, arrayed for battle. It was neither Germanic horde, nor Carthaginian Hannibal with his war elephants. This was a military threat never before faced by the Republic in its 500-year history. A Roman army, six veteran legions, 25,000 men. Just days before, this army had sat awaiting deployment to the East, to bring war to the Republic's great generational enemy, Mithridates of Pontus, the Poison King. But in the Republic, the military was political, and the political was corrupt. A rival general had conspired with pliant politicians to strip the Eastern command from the Senate's designated appointee.

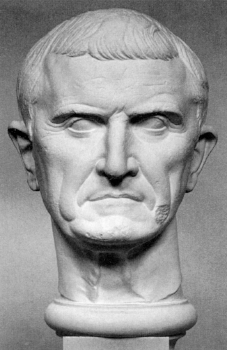

Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Dictator.

Sulla the Golden-Haired

His enemies underestimated Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who would have his command, whatever the cost. With his signature golden-red hair and blue eyes, Sulla was by turns charming, vindictive, brilliant, mercurial, and brutal. A patrician of an ancient but impoverished house, Sulla drank hard and went to bed with Roman ladies and Greek actors alike. He was unlike anything the Republic had ever seen, and he would make himself its master, all while laying the groundwork for its ultimate collapse a generation later.

Sulla's political ascendancy came at a time when the loyalty of a legion was above all to its commander, not to the state. So when the state cheated Sulla out of his Pontic command, enraged at both the affront to their general and the lost opportunity for plunder, Sulla's most loyal troops followed him across the sacred boundary of Rome in a breach of a most ancient tradition. Sulla captured Rome, driving out his rivals and declaring them enemies of the state. He put in place a makeshift political settlement before setting off to begin his Eastern campaign by laying siege to Pontus-controlled Athens.

Terror

The Republican mode of government, its system of checks and balances subject to facile subversion, was accelerating toward a critical existential moment. The institutions of state, were made for a different and simpler time. But they remained jealously preserved by the small slice of historically entrenched interests that controlled them, even as they proved increasingly inadequate. At the same time, state policy itself cloaked the traditional politician-general in the raiment of the warlord, placing the Republic in the crossfire of armed and ambitious rivals.

And nobody was as ambitious, as bold, or as ruthless as Lucius Cornelius Sulla. After spending five years fighting Mithridates, his enemies back in charge of the city, Sulla a second time marched his legions on Rome, vanquishing resistance in a ferocious battle at the city gates.

Sulla at the Colline Gate. Second march on Rome.

The following day, Sulla convened a meeting of the Senate, where he treated the assembled body to a spectacle of unimaginable violence. As he spoke, in calm and measured tones, screams of terror emanated from outside the meeting hall, causing a panic among the Senators. To assuage them, Sulla casually remarked, "it is just some criminals receiving their punishment." In fact, his soldiers were butchering 6000 prisoners of war, penned into an enclosure, down to the last man.

Now unchallenged, Sulla compelled the Senate to appoint him dictator, singularly in control of the state with no term limit. This was unprecedented in Roman history, where the dictatorship had only been employed as a temporary measure in times of military crisis. Sulla brooked no dissent from his program. When one of his most valued lieutenants ran for office despite Sulla's contrary command, Sulla had the man summarily beheaded in the midst of the crowded forum. He then announced to the assembled masses that he himself had ordered the murder, simply because the man did not obey him. He then told the crowd a parable of a farmer, whose jacket was infested by lice. Twice, said Sulla, the farmer had left his plowing to clean his shirt, but when the lice returned again, he burned it to avoid further interruption. "I warn those who have been overcome by me twice not to require fire the third time."

In the Senate.

His vengeance unremitting, Sulla began a program of bloody proscriptions, purging the aristocracy of political enemies, real or imagined. And because a proscribed individual's fortune was forfeit, there was money to be made for Sulla and his most cynical adherents. Many were proscribed, not because of political opposition to Sulla, but simply to appease his rapacious loyalists. Upon seeing his name on Sulla's lists, one victim famously bemoaned "my Alban villa pursues me!" According to Plutarch, "he had not gone far before a ruffian came up and killed him." One of the nastiest of Sulla's men, Marcus Licinius Crassus, became fabulously wealthy taking advantage of frequent urban fires--some of which he may have started himself--sending his private fire brigade to the rescue, but only after forcing the building owner to sell him the property at a knock-down price.

"If Sulla Could Do It, Why Can't I?"

The irony of Sulla is that, despite his use of radical means en route to power, once there his agenda was reactionary. Sulla sought to refortify the political power of the Senatorial class, and instituted a new constitution directed to that end. Ever the Republican, when he was satisfied with his new political order, he voluntarily resigned the dictatorship, and retired with the love of his life--the actor Metrobius--to a life of drinking and memoir-writing in the country. Two years later, he was dead.

The problem, of course, was that Sulla's reforms were only as strong as the man who made them. The Republican system remained one that could be gamed, and it remained inadequate for the governance of empire. His constitution was soon undone, but his legacy of political violence and civil war had lasting effects, undoubtedly accelerating the Republic's demise. A generation later, an even more ambitious and brilliant statesman-general, Gaius Julius Caesar, would cross the Rubicon river with his own legions and pursue his rival Pompey, he whom Sulla had affectionately called adulescentulus carnifex ("teenage butcher"), to a decisive battle in Greece. Indeed, Pompey himself had remarked, in reference to Sulla's marches on Rome, "if Sulla could do it, why can't I?" Within another generation, Augustus would close out the Republican period, consolidating in himself the power of the state, and usher in an Empire that would last for half a millennium.

The lesson of Sulla and the end of the Republic is a lasting one. It shows how a cynical and determined actor can, through violation of convention and precedent, take advantage of a flawed political system and turn it toward his own ends. And while he may not ultimately overturn the existing political order, by rendering imaginable the previously unthinkable, he can prime the conditions of state for a sea change at the hands of a more visionary successor.

The reasons I write of Sulla now should be obvious enough to anyone with an Internet connection and/or a pulse. The role of Sulla in the upending of a political order resonates today. Some parallels are real, some are mere phantoms, and in many ways circumstances two millennia apart simply are not capable of comparison. But we should take what we can from history when it has something to show us. The fall of the Roman Republic still speaks to us, and we would be wise to listen.

Next time, we'll return to our regularly scheduled programming.