Can it be gainsaid that Tokyo is the most magical place on earth? I should think not, but I recognize this is a matter of opinion, and others might have a different view of “most magical,” or even of what qualifies as “magical” in the first place. Disneyland calls itself the “Magic Kingdom,” at least implying that it has some claim to “most magical.” But in what respect is the manufactured Disney experience “magic,” if I may put the question to the Walt Disney Corporation? I concede Disneyland could be “magical” for at least some small children, but I imagine an adult might use other words to describe it. “Exhausting” and “expensive” come to mind. I’ve never been to Disneyland—or even wanted to go, for that matter—so I’m not exactly an authority. It’s an educated guess on my part, but I think the odds are good I’m in the ballpark.

Tokyo Foods. (1) Spicy yuzu-chintan ramen; (2) Monjayaki; (3) Umibudo; (4) Japanese Denny’s

One thing I can say with some assurance is that the Magic Kingdom does not enable its visitors to eat a dozen pieces of toro, for less than $30, twenty-four hours a day. If this was Tokyo’s only attraction, it would, in my view, give the city a reasonable claim to ''magical” status. And surely the kid’s pancake set at any of hundreds of Tokyo Denny’s is more kawaii than any comparable breakfast entree at a Disney theme park. Now consider the fact that in Tokyo, at certain cafes, a hedgehog will be delivered to you with your coffee, so you can spend time together while enjoying your drink. I suppose this is as it should be. Why, after all, can’t I rent a hedgehog as a beverage accompaniment here in our California metropolis? No doubt our public health authorities wouldn’t be as sanguine about the whole thing as their Japanese counterparts. Perhaps they should revise their crabbed view of what constitutes a sanitary beverage experience. Until they do (i.e., never), one must make haste to Edo to satisfy the innate human need for hedgehog companionship in a public eating establishment.

Tokyo Sky Tree. Four views.

The same can be said for the many species of animal cafe found in Tokyo. Owls, falcons, reptiles and now—eureka!!—mameshiba cafes! What is this, you ask, and why am I so excited about it? Mame is Japanese for “bean,” so these are “bean shibas”—miniature shiba inu dogs. When planning our trip last month, we naturally settled on the mameshiba cafe as our chosen pet cafe destination, what with the obvious business nexus and all. It’s not like we have some unmet need to spend time surrounded by Japanese dogs. There are, after all, two of them under my feet as I type; my life is lived in a shiba cafe of sorts, albeit one where I’m responsible for cleaning up the dog hair at the end of the day. Of course, our shibas are not mame, and we are cognizant of the inverse relationship between size and cuteness, so the mameshiba cafe had the potential to unlock new levels of dog experience.

Mameshiba Cafe. Doggie diapers, dog staff, and Shiba Ramen.

Miscellaneous Japan. Clockwise from upper left: (1) Sake sake sake; (2) Street-facing tank at fugu (puffer fish) specialty restaurant, Asakusa; (3) Oshiri Tantei, aka Detective Butt, hugely popular children’s book series; (4) Wagyu yakiniku restaurant, Asakusa.

In planning the trip, we assumed we’d only have time to visit one pet cafe. By happenstance, we ended up visiting three. The hedgehog cafe was on a main street two blocks from our hotel in Asakusa, and was ideally positioned when we needed and afternoon pick-me-up of caffeine and sugary drinks. And there was an owl cafe underneath the mameshiba cafe, and discount tickets for the former came with tickets to the latter. Of course I wanted to see owls again. I’ve chronicled the owl cafe phenomenon here before (magical!), although I now have a concern over the wild proliferation of Tokyo owl cafes since our first visit to one in 2015. Owl-sploitation may be on the rise. The original cafe we visited (Fukuro no Mise) appeared to take really good care of the owls, with three handlers present and mediating all customer-owl contact. This time, the cafe was operated by a single cashier sitting at an entry kiosk, with the owls attached to isolated perches along the route through a sort of forest trail setting. Several of the owls were not comfortable with human contact, which isn’t surprising given that visitors are left half-unsupervised as they wander the trail. Who knows what people do to them, or how they’re treated after hours. We left feeling a bit sad and uneasy about the whole thing. This owl cafe (and I assume many similar copycat cafes) was definitely not magical, although I’d gladly go back to one where the animals are treated well.

Sushizanmai. I love this chain of sushi restaurants in Tokyo. At least some are open 24 hours a day, and the quality control is excellent. The “Magurozanmai” costs 3000 yen—that’s only $27 with current exchange rates!

The mameshiba cafe was a decidedly happier place. A “dog staff” of twelve, the youngest ones wearing doggie diapers, roamed around, played, and snoozed—the kinds of things dogs do. There was plenty of human staff, and the setup left little risk of customer mistreatment of the dogs. Almost all the dogs were females, sensibly, because the last thing anybody needs in a small, crowded room is a dominance contest between testosterone-addled males. The dogs may be mame, but sharp teeth are sharp teeth.

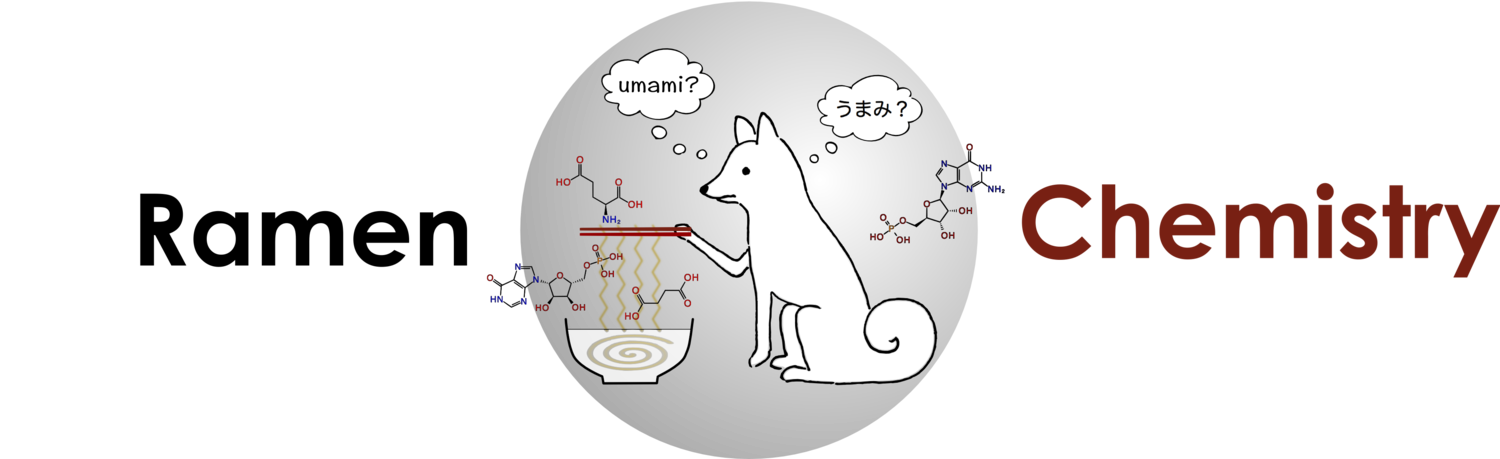

Now just to be clear, our time in Tokyo was not all animal cafes, but when you’re with a six-year-old, choices have to be made. Other such choices included soft serve ice cream (aka sofuto kuriimu) at least once a day and, with great sadness, turning away from the Vermeer exhibition in Ueno Park. If you’ve ever seen a Vermeer in person, you understand my disappointment. On the other hand, we only noticed the Vermeer event en route to the National Museum of Nature and Science, which is a world-class science museum. Astoundingly, it had a floor dedicated entirely to chemistry including—much to my delight—exhibits on stereochemistry and atomic orbitals!

Chemistry. Clockwise from upper left: (1) Stereochemistry - enantiomers; (2) carbon fullerene; (3) periodic table; (4) atomic orbitals.

Kindergartner in Tokyo. Ice cream, hedgehogs, and endless places to make a face.