We're still talking about soup. We've covered pork and chicken, so now let's talk about the other key flavor elements: seafood and mushrooms.

If you've eaten much Japanese food, you know how important seafood and mushrooms are throughout the cuisine. And when I talk about seafood, I'm not thinking about obvious things like sushi. I'm thinking about dried fish and seaweed. I'm thinking about dashi.

Dashi basics. Niboshi, kombu, katsuobushi, clockwise from upper left. Photo credit: http://www.japanesecooking101.com/dashi/.

If there's any concept that is truly elemental in Japanese food, it's dashi. You may not have heard of dashi before, but if you've eaten miso soup you've tasted it. Ever had agedashi tofu as an appetizer at a sushi restaurant? Yep, it's the same dashi. Dashi is simply everywhere in Japanese cooking.

Agedashi tofu. Photo credit: http://japaneseizakaya.blogspot.com

The simplest explanation of dashi is that it is a broth made from a variety of umami-heavy ingredients from the ocean. Most commonly these are kombu (a kind of kelp), katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes), or little dried fish like niboshi (a type of immature sardine). Dashi can also be made with mushrooms, with shiitake being among the most common.

You make dashi by soaking one or more of these ingredients in room temperature water for an extended period of time; you can also boil them for a shorter period. In either case, you filter off the source material once the extraction process is complete, and you are left with a clear broth popping with umami. Some dashi recipes are here, here, and here.

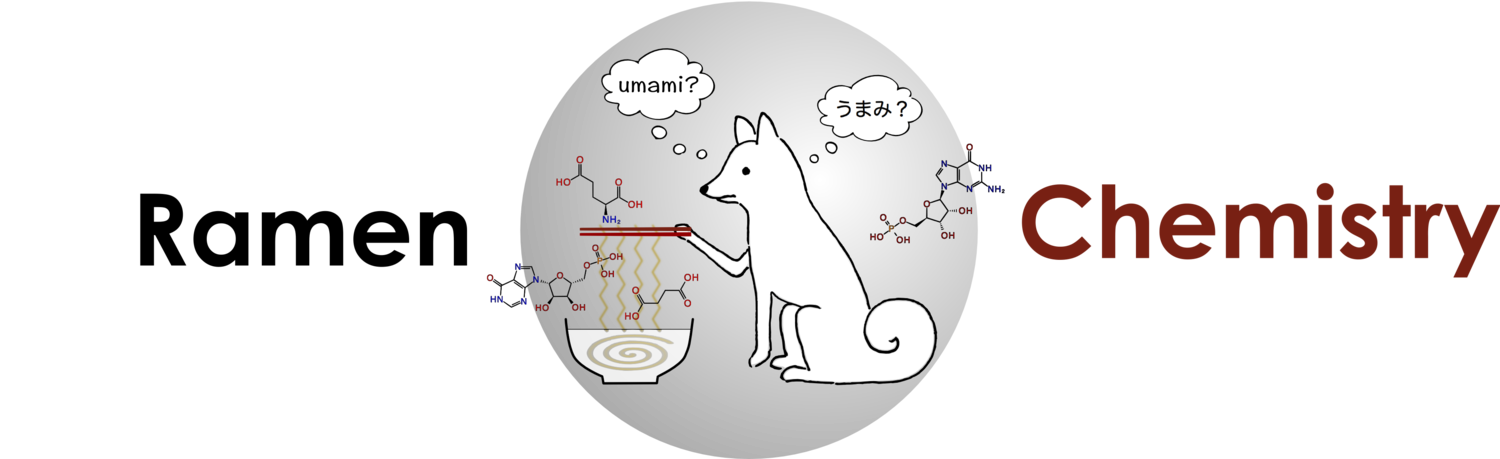

And when I say these ingredients are umami-heavy, I mean it. Kombu has more free L-glutamate (the molecule responsible for umami) than any other food source, at least according to the Umami Information Center. Meanwhile, katsuobushi and niboshi are super-enriched in umami-enhancing ribonucleotides. I'll explain that cryptic term “umami-enhancing” in a future post. There's a fascinating molecular-level relationship between glutamate and certain ribonucleotides that underlies the human umami response. If you want to know what these molecules look like, just look up at the Ramen Chemistry logo. L-glutamic acid is hovering above the chopsticks, while the ribonucleotides are the ringed structures flanking our ramen-loving shiba inu.

Ramen School. Fish heads and tails being grilled for use in a guest chef's soup (left). Soaking niboshi to make dashi soup (right).

Now that you understand dashi, let's bring it back to ramen. Dashi is widely used in ramen, especially in the clear chintan ramens I described in my last post. You can incorporate dashi into chicken or pork-based ramens by boiling the bones in a pre-prepared dashi broth. When you combine the unique and umami-loaded flavors in dashi with the rich flavors and textures of pork or chicken, you will have a real Japanese food experience. The beauty of ramen is that it brings these elements together with the potential for nearly unlimited variation. Top your ramen with some hot chicken oil (chiyu), marinated pork belly (chashu), and an ajitama (marinated soft-boiled egg), and you have yourself a serious meal.

Speaking of which, Hiroko spent the day yesterday making a dashi chintan and some really fatty chashu. It's now Saturday at 5:30, so I'm thinking it's time to migrate to the kitchen and eat some ramen.

Update. 9:01 p.m. Today's ramen was light in body, yet with the deep and complex manifold of flavors from our use of katsuobushi, kombu, shiitake mushrooms, chicken, and pork. It was topped with chiyu, chashu, menma, and ajitama, and garnished with tokyo negi, mizuna microgreens, and lime zest. The lime zest added an interesting freshness, but should have been shaved more finely. We'd love to try yuzu for this application. Eggs were overcooked by just a few seconds (it's a very fine line to get the texture right). Take a look:

Dashi chintan, with mizuna microgreens and lime zest. Photo credit: me.