I am reminded there is more to life than lawsuits and childcare and learning how well the Second Law of Thermodynamics--i.e., the entropy of a system always increases, the inexorable trend in the universe is toward disorder--explains the experience of managing and retaining a restaurant staff. We can always return to Japan, the country that produces the "Moist Diane" line of hair-care products, and it is amazing.

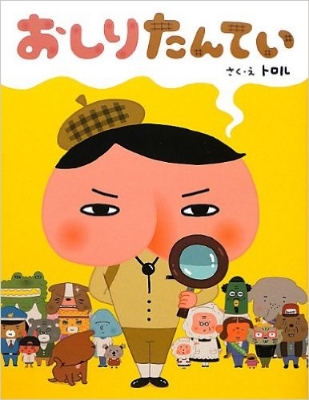

Last week, a small but very satisfying slice of Japan arrived in my house. Hiroko went kids book shopping in Kinokuniya, a Japanese bookstore in SF Japantown, and came back with the delightfully weird Detective Butt (Oshiri Tantei in Japanese, and in some places translated as The Butt Detective or The Bum Detective). I couldn't read the title when Hiroko thrust it in front of me, but I could see what was on the cover.

I did a double-take. I said to her, "is his head really a . . . butt?" "Yeah," she said, "his name is Detective Butt." And so it is, reader, so it is.

Only in Japan. Japan is an amazing filter of foreign culture. Here, the input is Sherlock Holmes. The output is Detective Butt. Also, should we be surprised that of the two translations currently on the market, one is French? The other is Korean.

Detective Butt, believe it or not, is a completely serious and very smart book. It's a Japanese kids repackaging of Sherlock Holmes, wherein the Holmes character just happens to have a butt crack in place of a nose and mouth (although I presume there's a breathing apparatus buried in there somewhere). But otherwise he's completely Holmes: logical, sophisticated, intense and intellectually rigorous. His eyes (one on each cheek) are fierce. The book takes kids through a surprisingly thorough investigation of a candy theft from a sweet shop. It forces them to examine evidence and identify witnesses on the way to figuring out who did the crime. Detective Butt is joined by a cast of cute characters, like a dog policeman and something that looks like a cucumber mated with a balding, goateed middle-aged man. There's even a scene in a ramen shop!

Perhaps you've started to wonder where the punchline is, am I right? I mean, why is his head a butt? Is that part of the story? What's the point of the whole thing? That's what I asked Hiroko, at least. "It's just that his head's a butt," she responded. So that's how it is.

And that's where we come to Japan, possibly the only country in the world where Detective Butt could not only be created, but end up a bestseller. My other comment to Hiroko was to the effect that there is something so completely Japanese about this book. Like, if some nation is going to make a book like this, it's of course going to be Japan. She agreed.

But why do we think this? What's so Japanese about it? Sure the animation style is definitely Japanese, but it's more than that. It's the book's ability to make the butt/head so conventional, so incidental to the story. The whole thing is just so matter-of-fact. In this world, there's nothing unusual about a man with a butt for a head. The butt is unremarkable and unthreatening. It's just human anatomy, it doesn't have to be sexual or fecal.

Makes Complete Sense. Two Butt Detectives, Japan (L) and America (R). The one on the right is what you find if you search "Detective Butt" on Google. If you want the one on the left, try searching "Oshiri Tantei."

Japan is a country where the urinal stalls on trains sometimes have a see-through window rather than a "vacant/occupied" sign. People would freak out in America. To see the back of a man peeing on public transportation would certainly herald the End Times, I have little doubt.

On my first trip to Japan 13 years ago, we were in Tokyo Station the morning after I arrived. I announced a need to use the bathroom. Hiroko said "do you know what's in there?" She laughed and called out "good luck!" Inside, I found myself face-to-face with a squat toilet. What madness is this? What am I supposed to do with that? Sensing my obvious confusion, a cleaning lady grabbed me by the shoulders and thrust me toward the next stall, which housed a western toilet. In the end, I'm not sure which part surprised me more: that squat toilets were a thing, or that a lady was in the men's room tidying up in and directing confused tourists to the proper facilities.

And let us not forget about the toilet slide museum exhibit where, according to Huffington Post, children "are greeted by cartoon stools and singing, interactive toilets that guide them through lessons about what feces are made of, where they go and how different toilets are used around the world." Oh, and the human body exhibit where museum-goers walk into a giant inflatable butt.

I repeat, completely different sensibilities.

Scenes from Detective Butt.

It's this innate Japanese neutrality toward its potentially scatological subject matter that makes this book possible. Combine that background with the Japanese ability to make pretty much anything cute (see, e.g., poop emoji and toilet/butt museum exhibits, supra), and Detective Butt starts to appear more inevitable than anything else.

Brilliantly, Detective Butt sustains the joke with barely a wink at the reader until our sleuth finally corners the culprit (a pig) in a gritty back alley at the end of the story. Now comes the punchline: Detective Butt deploys his secret weapon--a potent blast of facial flatulence--to disable the crook. So a butt is a butt after all. But even then, as soon as the air is clear, Detective Butt is back to his life of sophistication, soaking in a hot bath, then enjoying tea and potato cakes in his bathrobe.

When I told Hiroko I could imagine Detective Butt as a whole series of books, she informed me that there are already seven of them! Of course there are.

Google Translate! While searching, I found this Japanese bookstore page announcing a Detective Butt event. Clicked translate, and voila, this!