So far, we’ve been navigating the basics of ramen here at Ramen Chemistry. Ramen is our product after all, so that's how I kicked off this blog. But Ramen Chemistry is not a food blog, per se. It’s about every aspect of the ramen business. Once Shiba Ramen secures a physical space (hopefully soon), our lives are going to revolve around getting the business open, and Ramen Chemistry is going to reflect the the diverse things we'll be doing to make it happen.

But here in the last days of (relative) calm before our fire drill starts, I want to take a short detour into the world of science. Chemical biology and food science, that is. I want to tell you about the molecular basis for the human umami response. This is real, current science and it relates to ramen. Let’s get started!

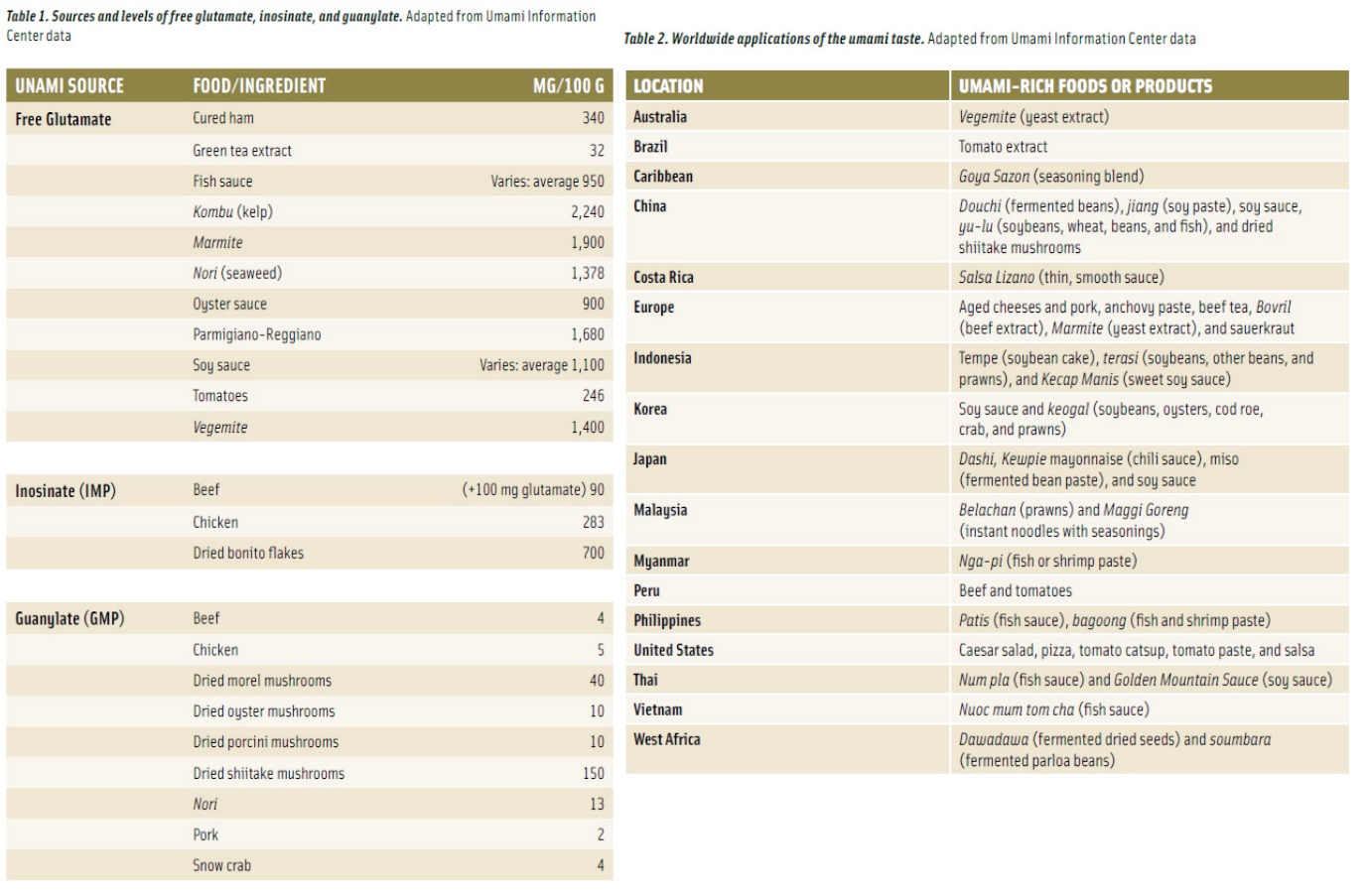

MSG. Monosodium glutamate. This unnecessarily controversial compound is naturally abundant in many foods we eat every day (see below).

What Is Umami?

Umami (literally "delicious taste" in Japanese) is, along with sweetness, saltiness, sourness, and bitterness, one of the five basic tastes. It is often described as having savory or mouth-watering quality. The umami response is triggered by free L-glutamate (one of the 20 naturally occurring amino acids, the building blocks of proteins), usually in the form of its sodium or potassium salt. The sodium salt is, of course, monosodium glutamate, MSG. And, as we'll discuss, the glutamate-induced umami response is strengthened when either of two ribonucleic acids (the building blocks of RNA), guanylate or inosinate, is present. Foods that contain these chemicals deliver umami. That's it.

Umami Foods. Left image shows amounts of glutamate, inosinate, and guanylate in everyday foods. Right image shows umami-rich foods worldwide. These images were taken from this very informative article.

I remember the first time I read about umami. It was in some magazine (I think on an airplane) about a decade ago. The article described umami as the “elusive Japanese fifth flavor.” That phrase “elusive” persisted in my thinking for years, in part perhaps because the article’s phrasing—Japanese fifth flavor—left me with the impression that umami was somehow a uniquely Japanese phenomenon. If that was true, umami may well be elusive to anyone not steeped in Japanese food and culture.

Umami is elusive, but not because it’s foreign. Although it’s perhaps more prevalent in Japanese cuisine, with its heavy use of high-umami ingredients like kombu and dried fish, umami has a long history in Western cooking. The ancient Romans were wild about garum, a fermented fish paste that was full of umami. A recent article explains that "like Asian fish sauces, the Roman version was made by layering fish and salt until it ferments. There are versions made with whole fish, and some just with the blood and guts." The process "creates a fermentation environment that releases more of the protein, making garum a good source of nutrients" and giving "it a rich, savory umami taste." A food historian is quoted as saying that garum is "very, very flavorful. It explodes in the mouth and you have a long, drawn-out flavor experience, which is really quite remarkable."

Garum Amphora. Floor mosaic from garum shop in Pompeii. The favored condiment in ancient Rome was an umami-heavy paste made of fermented fish guts.

Today, we're wild about pizza, burgers, bacon, roasted tomatoes, oysters, parmesan cheese. Have you ever eaten at Umami Burger? Their concept is to make burgers that are umami-maximized. They do it by invoking non-traditional burger ingredients (and combinations thereof). They have umami-maximized ketchup on the table, and a very nice appetizer plate of high-umami pickles. I've eaten there a couple times, and there's a definite difference in how these burgers taste. Eating one and thinking about its flavor compared to a normal burger is actually a pretty good way of isolating the umami flavor and getting a better sense of what it is.

Umami Burger. Parmesan frisco, shiitake mushrooms, roasted tomato, caramelized onions, umami house ketchup.

Umami is elusive because of its relative subtlety. It doesn’t jump out in the obvious way the other four flavors—sweet, salty, sour, bitter—do. Think about all of the times you’ve thought something was too sweet or too salty. You probably never thought that something has too much umami. Umami is also elusive, I think, because we take umami flavors for granted. We don’t have the “umami” concept in western culture, and we’re just not used to talking about our food in these terms.

I like to think of umami this way: imagine the last time you ate a really good slice of pizza. You were pretty into it, right? It was hot, the crust was crispy, and it had so much flavor. You had a hard time stopping after a few pieces. What flavors did you taste? There was some sweetness and sourness in the tomato sauce, and maybe something was a little bit salty, but of the flavor in that slice of pizza, how much of it can you really assign to sweetness or saltiness, let alone to sourness or bitterness? All the pizza’s indefinable savoriness, all that flavor that’s not sweet or salty, sour or bitter—that’s umami. I'm oversimplifying it a bit, I'm sure, but you get the idea behind this thought experiment. Next time you have pizza or a bacon cheeseburger, think about this formula and maybe umami will start seeming less elusive:

Umami = Total Flavor – (Sweet + Salty + Sour + Bitter)

Maybe you still can’t totally put your finger on it, but by eliminating sweet, salty, sour, and bitter, you see that something else is hard at work making your pizza taste so good. That’s umami.

Next time, I'll explain how umami was discovered and how umami happens down at the molecular level.